Beyond what the eye can see

Fashion illustration is a kind of distorting mirror in which one sees—by some magic trick—a more precise reflection. In the words of Marc-Antoine Coulon, the creative process of the illustrator involves going “beyond what the eye can see.”

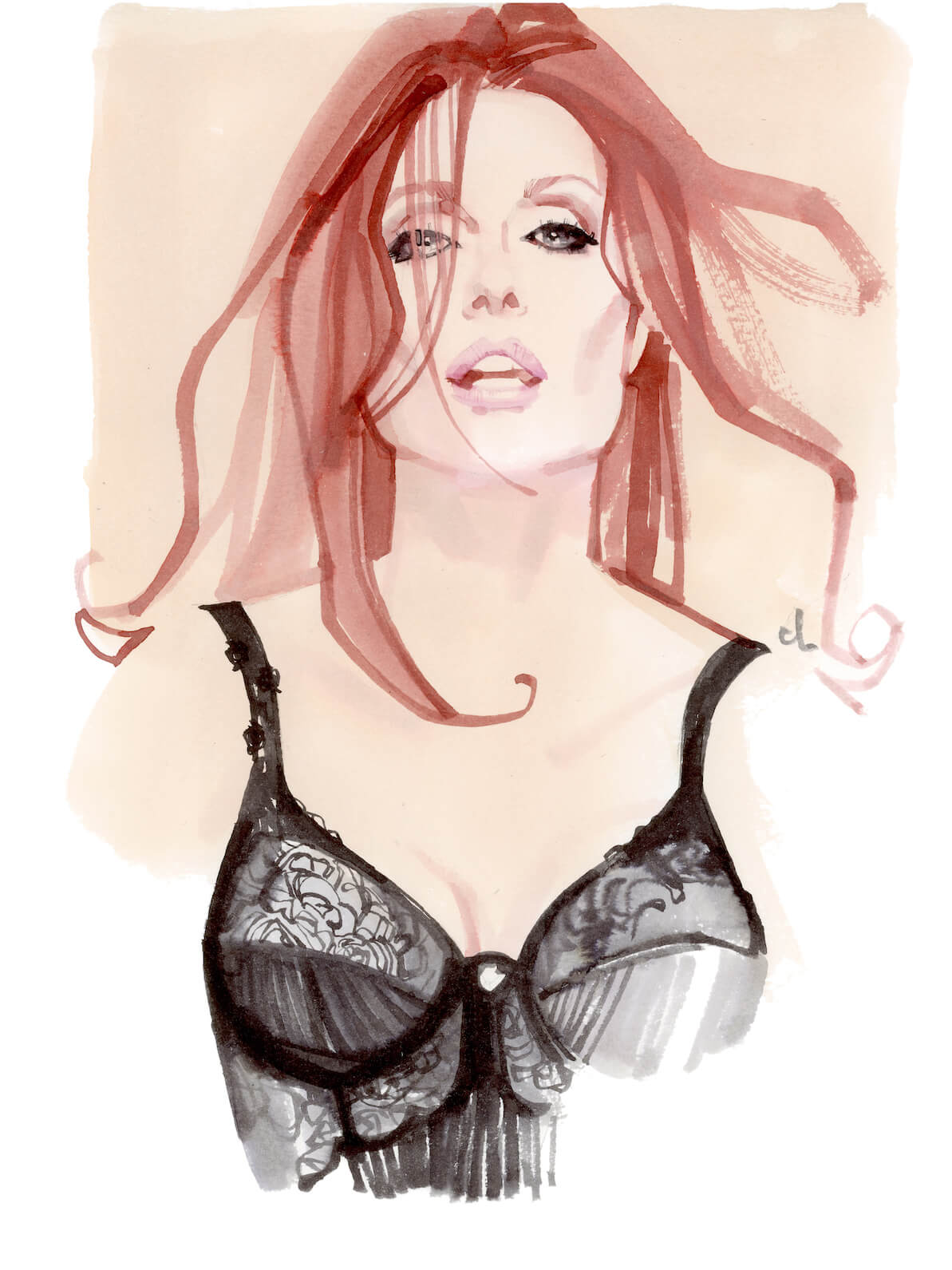

Catherine Deneuve by @marcantoinecoulon

Mr Coulon got his start working in the music industry. “It was at the end of the CD era and they had not yet realised that they could go back to vinyl records. It was a dying industry and one that didn’t like (visual) artists. It was difficult to have a vision…because they wanted me to be like a smartphone app and turn any photo into a drawing, which freed them from paying copyrights to photographers. So we weren’t really on the same line. But I love a challenge and it’s difficult to be creative when you have no boundaries. In the music industry, I had a lot of boundaries. It was a good education.”

An education that led him into the pages of Paris’s most storied glossy magazines. Having his work featured in Madame Figaro felt a bit “like coming home” to Mr Coulon, who devoured the magazine as a child, with special affection for the work of Rene Gruau, perhaps the 20th century’s most influential and revered illustrator. Regarding illustration, Gruau felt that “the more you move away from the expected and the traditional, the better it is.” Mr Coulon’s work triumphs because it blends tradition and modernity. His portraits have a sharpness of expression that channel the sitters’ famous traits (Gaultier’s “Mona Lisa grin,” Deneuve’s cryptic aloofness, the radiant intelligence of Ines de la Fressange). Parts of the image attract the eye with precision and detail while other parts seem to disappear into the whiteness of the page or an expressionistic slash of colour.

Couture collection 2019 for © Madame Figaro by @marcantoinecoulon

Regarding Gruau’s dicton, Coulon says: “That is the big challenge: to move away from what is expected. Most clients have an idea of what they want and it’s your responsibility to teach your clients that you can do so much more. Most of the time I do both exactly what they want AND another thing with more creativity.” Commercial work requires a slightly tweaked creative process: “Often (the clients) want me to do sketches, but I’m not very good at that. It’s like making love: I cannot make love ‘just a little’. For me, making images is very sensual and I cannot indulge ‘just a bit’. Even my sketches are almost like final images. The client won’t be able to imagine the final product from pencil sketches. I want my images to be able to defend themselves. I strongly believe in the “wow effect” and it’s difficult to get that from just a few pencil sketches.”

Mr Coulon’s images always leave a space for the viewer to project—to connect the dots, so to speak. He has a generous and affectionate esteem for his spectators’ intellect. “You have to trust your viewers—because they are intelligent—that they will be able to build on your hints. When you prepare an exhibition, (the artwork) is all yours, until the moment they are hung on the walls and the visitors start to come into the room. Then they’re not yours anymore. They have a second history and it’s one that, perhaps, you didn’t intend. It all has to do with mutual trust: the viewer has to trust the artist and the artist has to trust the viewer. Hopefully you’re good enough to provide the right hints.”

Julianne Moore by @marcantoinecoulon